The wagons weighed from 1,000 to 1,400 pounds and carried loads between 1,500 and 2,500 pounds.

The wagons were ten to twelve feet long, four feet wide, and two to three feet deep, with fifty-inch diameter rear wheels and forty-four-inch front wheels made of oak with iron tire rims. Most used farm wagons that had been modified for long-distance travel, including strengthened axle trees and wagon tongues and wooden bows that arched over the wagon box to support canvas or other heavy cloth covering. Travelers generally walked alongside wagons full of their belongings and foodstuffs. When smaller groups combined, leaders shared duties and the authority for keeping order. After 1846, travelers could make their way overland on the Barlow Road from The Dalles, around Mount Hood, and directly to Oregon City on the Willamette River.įamilies and individuals on the trail typically traveled in companies that had twenty-five or more wagons, with one or more individuals providing general leadership. In Oregon, the trail passed through the Powder River and Grande Ronde Valleys, over the Blue Mountains, and down the Columbia River to The Dalles, where many rafted their wagons and belongings to the lower Columbia River Valley.

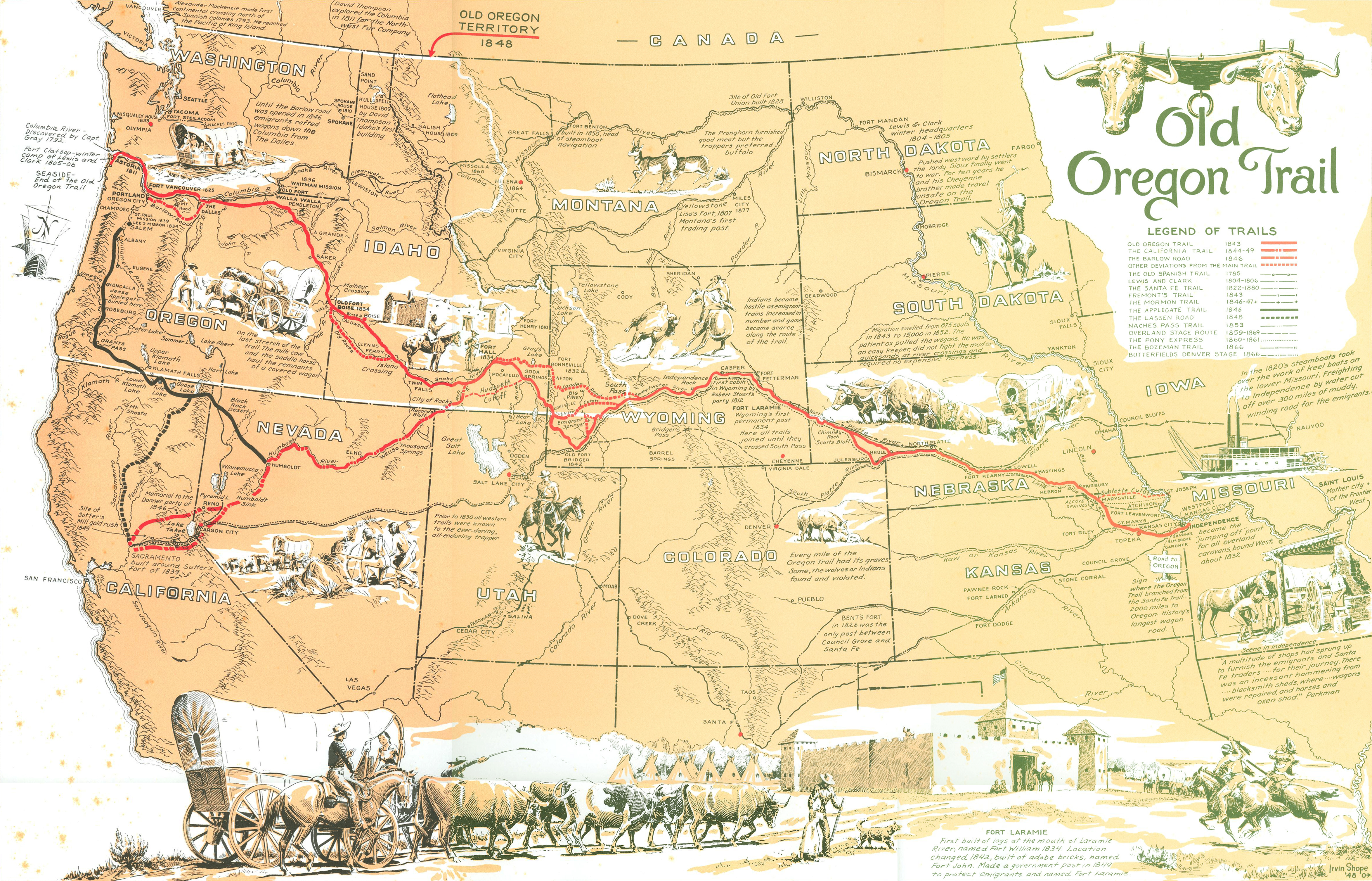

The trail followed the Missouri and Platte Rivers west through present-day Nebraska to South Pass on the Continental Divide in Wyoming, then west along the Snake River to Fort Hall in eastern Idaho, where travelers typically chose to continue due west to Oregon or to head southwest to Utah and California. The journey took up to six months, with wagons making between ten and twenty miles per day of travel. Between 18, from 300,000 to 400,000 travelers used the 2,000-mile overland route to reach Willamette Valley, Puget Sound, Utah, and California destinations. The Oregon Trail has attracted such interest because it is the central feature of one of the largest mass migrations of people in American history.

The trail continues as the principal interest of a modern-day organization-the Oregon-California Trails Association-and of major museums in Oregon, Idaho, and Nebraska.

The Oregon Trail was first written about by an American historian in 1849, while it was in active use by migrants, and it subsequently was the subject of thousands of books, articles, movies, plays, poems, and songs. It adorns a recent Oregon highway license plate, is an obligatory reference in the resettlement of Oregon, and has long attracted study, commemoration, and celebration as a foundational event in the state’s past. In popular culture, the Oregon Trail is perhaps the most iconic subject in the larger history of Oregon.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)